While Karijini National Park in Western Australia’s Pilbara region has earned an international reputation for its remote, rugged splendour, there is one deadly blemish on its border.

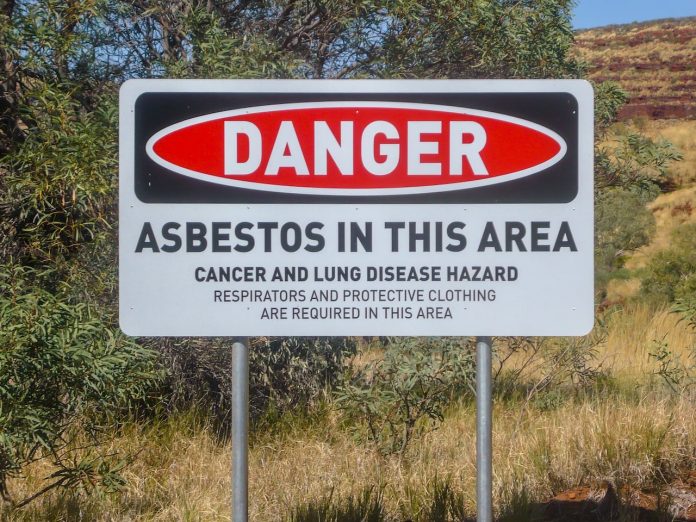

The Asbestos Diseases Society of Australia (ADSA) says the former asbestos mining town of Wittenoom, which borders the national park, is a potentially deadly threat to tourists and Aboriginal communities in the region.

ADSA CEO, Melita Markey says that despite health warnings as early as 1948 and the closure of the mine in 1966, people are ignoring the threat of contracting incurable mesothelioma cancer from asbestos dust particles at the former townsite.

Social media images of ‘adventure tourists’ playing in the deadly dust have led to a community education campaign by ADSA urging travellers not to visit Wittenoom.

“Sadly, we know the death toll from Wittenoom won’t stop until the visitors stop,” Ms Markey says.

There is no safe level of asbestos exposure, especially in relation to mesothelioma.

“It appears that many people today are unaware of Wittenoom’s legacy – that it continues to kill.”

There are still 14 properties with three owners in Wittenoom, yet to be acquired by the State Government, but Ms Markey does not know if any of them are living in the town.

She was very concerned though for the Traditional Owners of the Land the Banjima People who use the land as part of their cultural heritage.

“How do we protect them and respect their culture?” Ms Markey asks.

The Wittenoom Asbestos Management Area covers more than 46,500 hectares and includes the former townsite, Wittenoom Gorge and Joffre Floodplain and is classified as a contaminated site under the Contaminated Sites Act 2003.

Western Australia has one of the highest incidences of malignant mesothelioma per capita in the world. Nationally one person dies every 12 hours.

With a booming wildflower season under way Ms Markey said it was tempting for Pilbara residents and tourists to visit Wittenoom.

Based on ASDA’s monitoring of social media it was clear that tourists, photographers, campers, and even young families, are visiting Wittenoom every day.

“The mine and mill is the greatest example of workplace negligence in Australia, and second in the world to date,” she says.

“The contamination of the town and its surrounding gorges continues to kill traditional owners and visitors to the region.”

Wittenoom was established as a blue asbestos mining town in 1937 and since then asbestos dust has killed thousands of workers, their families and town visitors.

Alison Xamon MLC said in a 2018 speech to the WA Legislative Council that asbestos has been used primarily in WA’s building and manufacturing industries since the 1920s.

From 1943 to 1966 more than 20,000 people lived and worked at Wittenoom.

In 1993, it was estimated that 40,000 tourists were still visiting the area. This led concerned members of parliament to establish an inquiry into Wittenoom and Tourism.

A report tabled in 1994, by Larry Graham MLA found that Wittenoom was contaminated; 34 recommendations were subsequently made including ‘cleaning up the township and surrounding areas’.

“The report did not gain traction and today the town and surrounding areas are so contaminated, we are potentially looking at a new generation of asbestos diseases victims,” Ms Markey says.

“It is the microscopic fibres that you can’t see, that cause the most harm. People think if they stay away from the mountains of asbestos tailings or wear a Covid mask, that they’re protected – they are not,” she says.

Fibres lodge in the pleura of the lungs and/or in the gut if ingested, for decades, until mutations occur causing asbestos related cancer.

“These diseases would be preventable but for the indifference and the lack of corporate governance in allowing CSR to close the mine without cleaning up the environment.”

The thousands of victims and their families of the Wittenoom asbestos tragedy have never been formally recognised.

ADSA is hosting an online petition for a permanent memorial to be erected in Karijini National Park with the names of the thousands of Wittenoom workers, residents, traditional owners and their family members who lost their lives to asbestos-related diseases.

As the time between initial asbestos exposure and the onset of symptoms is from 20 to 50 years, ADSA will also be allocating space on the memorials for the hundreds, even thousands, of victims that have yet to be diagnosed.

Ms Markey says the memorial will serve a dual purpose: to acknowledge the sacrifice of lives in the desire for WA mining development and a meaningful deterrent for those tempted to visit Wittenoom.

Ms Markey says ADSA is exploring several ideas of what the memorial will look like, but what is most important is that any memorial will contain the names of all the victims and leave space for those continuing to emerge from the contamination created by Australia’s worst industrial disaster.

“The memorial of HMAS Sydney in Geraldton is something to aspire to,” she says.

The memorial is expected to cost around $250,000.

Ms Markey says there is no need to visit Wittenoom with many, much safer camping grounds near beautiful gorges and watering holes in the Karijini National Park.

To sign ADSA’s petition for permanent memorials in Perth and the Pilbara, visit www.change.org/Wit tenoomMemorial.

More than 3500 people have already signed the petition, which Ms Markey says is making an impact, but she would like to see a minimum of 10,000 signatures.

People wanting to register a loved one’s name for the memorial can do so at www.asbestosdiseases.org.au.