Fifty years ago, journalists from all over Melbourne were ordered to drop whatever we were doing and get down to the banks of the Yarra River.

Details over the phone from my boss at The Australian newspaper were sketchy: “There’s been some sort of tragedy.”

Approaching the scene, media cars were stopped at police roadblocks to check credentials. I was mysteriously waved straight through. Later, I found it was because my media-issue car was the same make and model as Victorian detectives’ cars.

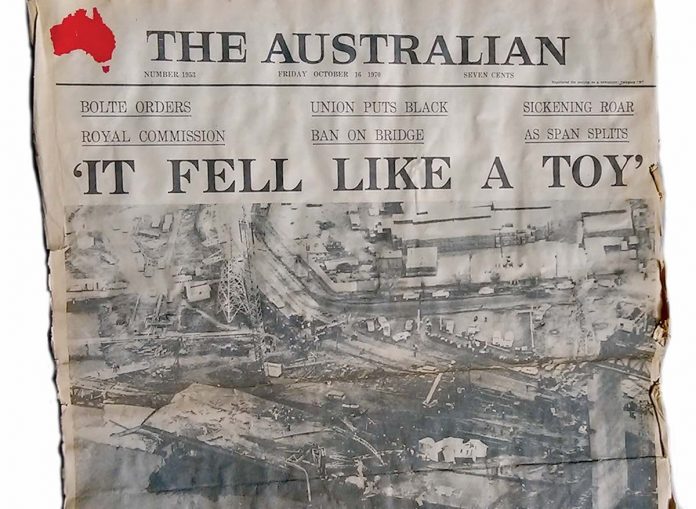

What confronted us, slumped in Yarra River mud, was an immense span of Australia’s fifth-biggest bridge. Two years into its construction, the West Gate Bridge – twice as long as Sydney Harbour Bridge – had given way. At 11.50am, a 112-metre span collapsed.

It slammed down 58 metres into the mud below, crushing workers just starting their lunch break underneath.

Emergency workers, police and TV cameras focussed on the twisted metal as medicos loaded bodies into a fleet of ambulances. It was a sickening sight.

Thirty-five construction workers were killed and 18 injured in Australia’s worst industrial accident.

Houses, fences and road signs blocks away were spattered with mud. The Salvos set up welcome stands to serve food and hot drinks to anyone who asked during the long hours into the next day.

As we reported: “Under the eerie glow of iodine lights, workers, rescue workers toiled in the twisted metal and workmen used blow torches to cut through the steel sections while cranes and skindivers stood by.”

Details began to unfold: About 10 workers rode the 2,000-tonne span down on its fateful fall but, incredibly, were thrown clear into mud or water, alive, although sustaining injuries.

Residents 20kms away heard the crash and buildings in Footscray hundreds of metres away were shaken.

Prime Minister, John Gorton, said: “I am sure the whole of Australia is shocked and saddened by the serious accident at West Gate Bridge. Please extend my deepest sympathy to all those families to whom this tragic event has brought such grief.”

Next day, Victorian Premier Sir Henry Bolte announced a Royal Commission to look into the cause of the disaster at the bridge, designed to become a vital link to the western suburbs and Geelong, 80kms distant.

Every working day for months we heard the smallest details outlined to the Royal Commission. Until 14 July 1971, when the Royal Commission attributed the failure of the bridge to two causes: the structural design by designers Freeman Fox & Partners and an unusual method of construction by World Services and Construction.

No-one was fined and no-one was jailed.

There was a difference in camber of 11.4cm between two half-girders that needed to be joined. It was proposed that the higher one be weighted down with 10 concrete blocks but the weight caused the span to buckle, a structural failure.

The job of joining the half-girders was underway when workers were told to remove the buckle. As the bolts were removed, the bridge snapped back and the span collapsed.

A witness described the deafening sound as something like a machine gun as thousands of bolts across the span shattered.

Construction resumed in 1972, a year after the finding. Six years later, the bridge was completed – 10 years in the making at a cost of 35 lives and $202 million.

Six twisted bridge fragments sit in the gardens in Monash University’s engineering faculty: “to remind engineers of the consequences of their errors.”

Commemorations are held every 15 October at West Gate Bridge Memorial Park, near the bridge that carries up to 200,000 vehicles-a-day.